SAMARIAN CEMETERY

Approximately 180,000 African Americans comprising 163 units served in the Union Army during the Civil War, and many more African Americans served in the Union Navy. Both free African-Americans and former slaves joined the fight.

The African American community of New Richmond, Ohio contributed proportionately a significant share to the cause of freedom and restoration of the Union. Black soldiers and sailors of New Richmond supported General Grant’s siege of Vicksburg in 1863. Five New Richmond men served in the same infantry unit, Company K of the 27th U.S. Colored Troops. Silas Owens, Joseph King, Jacob Thomas, Ila Houston and Alex Adams fought valiantly at Petersburg in July of 1864. These men are buried here in Samarian Cemetery.

After the war, many African American Union veterans established New Richmond as their home. In Citizens and Samarian Cemetery on Rt. 132 just outside New Richmond are the final resting places for 23 of these brave men.

Silas Owens Co. K 27th USCT (United States Colored Troops)

Joseph King Co. K 27th USCT

Samuel Brown U.S. Navy

George Sweetman Co. F 100th USCT

Jacob Thomas Co. K 27th USCT

Oliver Moore U.S.N. Milwaukee/ Sciota

Ila Houston Co. K 27th USCT

Henry Johnson U.S. Navy Avenger

Thomas Perry U.S. Navy Benton

Alex Adams Co. K 27th USCT

Lee Banks Co. I 9th U.S. Cavalry (Buffalo Soldier)

Peter Wilson U.S. Navy Kenwood

Jno. Robinson Co. G 6th USC Cavalry

Frank Dancy Co. H 5th USC HA (United States Colored Heavy Artillery)

Dennis Anderson Co. C 14th USCT

Henry Pewitt Co. H 13th Indiana Cav.

Richard Johnson Co. D 117th USCI (United States Colored Infantry)

William Wilson Co. C or G 16th USCT

George Bond Co. A 33rd Ohio Infantry

Phillip Willis Co. E 26th USCI

Henry Picquet Co. K 42nd USCT

Edward Graves Co. E 26th USCI

UNKNOWN Unknown

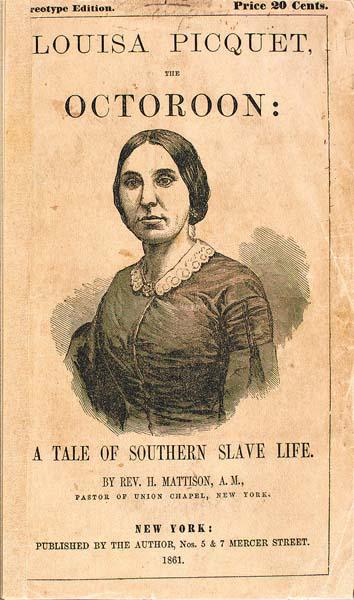

Louisa Picquet is buried in an unmarked grave in Samarian Cemetery presumably next to her husband, Civil War soldier Henry Picquet. The Picquets moved to New Richmond from Cincinnati in 1867. Before the Civil War, Henry worked as a janitor at the Carlisle Building at 4th and Walnut Streets. Louisa worked as a seamstress and operated a safe house for fugitive slaves at 135 Third Street near the current location of the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center. Henry and Louisa met in Cincinnati and were married in Zion Baptist Church in 1850. They were acquainted with Levi Coffin, the so-called “President” of the Underground Railroad.

Louisa was born into slavery in 1829 near Columbia, South Carolina. Her mother, Elizabeth Ramsay, was 15 years old. Louisa’s father was Elizabeth’s master, a white plantation owner by the name of Randolph. Elizabeth was herself the offspring of a relationship between her enslaved mother and white master. Louisa was 1/8 African American and by her appearance looked very much like her father and her half sister born to Randolph’s wife two months earlier. Not appreciating the visual reminder of her husband’s indiscretions, Mrs. Randolph insisted that both Louisa and Elizabeth be sold. They were purchased by David Cook and removed to Georgia. Several years later Cook experienced serious financial problems and moved his family and slaves to Mobile, Alabama to escape his creditors. They were eventually found and forced to sell their slaves to pay their debts. Louisa, now 14 years old, and her mother and 8 year old brother were put on the auction block separately. Mr. Horton from Texas bid the highest for Elizabeth and her son. When Louisa was placed on the block, Mr. Horton was outbid by a very determined Mr. Williams from New Orleans.

Separated from her family and oblivious to their fate, young Louisa was forcibly taken to New Orleans in 1842. Mr. Williams ran a hardware store and lived in a dingy small rental flat in the city. Although he threatened to kill her if she ever tried to run away, Williams promised Louisa her freedom upon his death. Each night Louisa prayed for her freedom to come soon. Before her prayers were finally answered, Louisa had 4 children by Williams. After Williams died in 1847 Louisa immediately sold all the furniture and belongings in the flat and purchased steamboat tickets to Cincinnati for herself and two surviving children. One died shortly after they arrived in Cincinnati.

Louisa settled in the black section of Cincinnati known as Little Africa. Daily she went to the public landing and inquired of travelers from the south seeking the whereabouts of her mother and brother. She also questioned the fugitives she sheltered in her house on Third Street before sending them on to the next station. She continued this for 8 long years until she finally met a traveler from Texas that knew of her mother and brother and their owner, Col. Albert C. Horton, the first Lt. Governor of Texas. With the help of Levi Coffin, Louisa was able to negotiate a purchase price of $900 for her mother’s freedom. The asking price of $1500 for her brother was beyond any reasonable possibility of raising the money. Louisa received small donations from local sources in and around Cincinnati. Coffin encouraged her to travel east to seek donations from wealthy abolitionists and sympathetic ministers and their congregations. Because of her appearance she had to carry a letter from Levi Coffin to verify her story. Louisa was successful in raising the money and was reunited with her mother in Cincinnati in October of 1860.

Henry Picquet could not return to his job as janitor due to a hernia he developed while serving in the 42nd U.S. Colored Troops in Tennessee. He died in New Richmond in December of 1889. Louisa Picquet died 7 years later in her home on Center Street in August 1896. Elizabeth Ramsay lived the remainder of her life with her daughter’s family on Center Street. Elizabeth is buried in another unmarked grave in Samarian Cemetery.

The African American community of New Richmond, Ohio contributed proportionately a significant share to the cause of freedom and restoration of the Union. Black soldiers and sailors of New Richmond supported General Grant’s siege of Vicksburg in 1863. Five New Richmond men served in the same infantry unit, Company K of the 27th U.S. Colored Troops. Silas Owens, Joseph King, Jacob Thomas, Ila Houston and Alex Adams fought valiantly at Petersburg in July of 1864. These men are buried here in Samarian Cemetery.

After the war, many African American Union veterans established New Richmond as their home. In Citizens and Samarian Cemetery on Rt. 132 just outside New Richmond are the final resting places for 23 of these brave men.

Silas Owens Co. K 27th USCT (United States Colored Troops)

Joseph King Co. K 27th USCT

Samuel Brown U.S. Navy

George Sweetman Co. F 100th USCT

Jacob Thomas Co. K 27th USCT

Oliver Moore U.S.N. Milwaukee/ Sciota

Ila Houston Co. K 27th USCT

Henry Johnson U.S. Navy Avenger

Thomas Perry U.S. Navy Benton

Alex Adams Co. K 27th USCT

Lee Banks Co. I 9th U.S. Cavalry (Buffalo Soldier)

Peter Wilson U.S. Navy Kenwood

Jno. Robinson Co. G 6th USC Cavalry

Frank Dancy Co. H 5th USC HA (United States Colored Heavy Artillery)

Dennis Anderson Co. C 14th USCT

Henry Pewitt Co. H 13th Indiana Cav.

Richard Johnson Co. D 117th USCI (United States Colored Infantry)

William Wilson Co. C or G 16th USCT

George Bond Co. A 33rd Ohio Infantry

Phillip Willis Co. E 26th USCI

Henry Picquet Co. K 42nd USCT

Edward Graves Co. E 26th USCI

UNKNOWN Unknown

Louisa Picquet is buried in an unmarked grave in Samarian Cemetery presumably next to her husband, Civil War soldier Henry Picquet. The Picquets moved to New Richmond from Cincinnati in 1867. Before the Civil War, Henry worked as a janitor at the Carlisle Building at 4th and Walnut Streets. Louisa worked as a seamstress and operated a safe house for fugitive slaves at 135 Third Street near the current location of the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center. Henry and Louisa met in Cincinnati and were married in Zion Baptist Church in 1850. They were acquainted with Levi Coffin, the so-called “President” of the Underground Railroad.

Louisa was born into slavery in 1829 near Columbia, South Carolina. Her mother, Elizabeth Ramsay, was 15 years old. Louisa’s father was Elizabeth’s master, a white plantation owner by the name of Randolph. Elizabeth was herself the offspring of a relationship between her enslaved mother and white master. Louisa was 1/8 African American and by her appearance looked very much like her father and her half sister born to Randolph’s wife two months earlier. Not appreciating the visual reminder of her husband’s indiscretions, Mrs. Randolph insisted that both Louisa and Elizabeth be sold. They were purchased by David Cook and removed to Georgia. Several years later Cook experienced serious financial problems and moved his family and slaves to Mobile, Alabama to escape his creditors. They were eventually found and forced to sell their slaves to pay their debts. Louisa, now 14 years old, and her mother and 8 year old brother were put on the auction block separately. Mr. Horton from Texas bid the highest for Elizabeth and her son. When Louisa was placed on the block, Mr. Horton was outbid by a very determined Mr. Williams from New Orleans.

Separated from her family and oblivious to their fate, young Louisa was forcibly taken to New Orleans in 1842. Mr. Williams ran a hardware store and lived in a dingy small rental flat in the city. Although he threatened to kill her if she ever tried to run away, Williams promised Louisa her freedom upon his death. Each night Louisa prayed for her freedom to come soon. Before her prayers were finally answered, Louisa had 4 children by Williams. After Williams died in 1847 Louisa immediately sold all the furniture and belongings in the flat and purchased steamboat tickets to Cincinnati for herself and two surviving children. One died shortly after they arrived in Cincinnati.

Louisa settled in the black section of Cincinnati known as Little Africa. Daily she went to the public landing and inquired of travelers from the south seeking the whereabouts of her mother and brother. She also questioned the fugitives she sheltered in her house on Third Street before sending them on to the next station. She continued this for 8 long years until she finally met a traveler from Texas that knew of her mother and brother and their owner, Col. Albert C. Horton, the first Lt. Governor of Texas. With the help of Levi Coffin, Louisa was able to negotiate a purchase price of $900 for her mother’s freedom. The asking price of $1500 for her brother was beyond any reasonable possibility of raising the money. Louisa received small donations from local sources in and around Cincinnati. Coffin encouraged her to travel east to seek donations from wealthy abolitionists and sympathetic ministers and their congregations. Because of her appearance she had to carry a letter from Levi Coffin to verify her story. Louisa was successful in raising the money and was reunited with her mother in Cincinnati in October of 1860.

Henry Picquet could not return to his job as janitor due to a hernia he developed while serving in the 42nd U.S. Colored Troops in Tennessee. He died in New Richmond in December of 1889. Louisa Picquet died 7 years later in her home on Center Street in August 1896. Elizabeth Ramsay lived the remainder of her life with her daughter’s family on Center Street. Elizabeth is buried in another unmarked grave in Samarian Cemetery.